Commemorative textiles: an African narrative of identity and power

Clothing and power identity is a complicated and varied subject that examines the relationship between clothing and social identity, and how clothes and fashion decisions can be used to exercise authority, convey social status, express identity, and affect perceptions (Akdemir, 2018). Across different societies and cultures, clothes have always been a key communicative factor in shaping power dynamics and political strength among rivals.

In ancient Greece and Rome, imperial China, the Islamic world, and Colonial America for instance, sumptuary laws were applied to control what people might wear based on their social ranks including wealth and political power to reinforce class boundaries (Wilson, 2016). Such stratifications mean that the poor class of the society was limited to simpler clothing, while the elite class was allowed to wear certain luxurious fabrics or color codes, which made them visible to the public and bolster their position of power and control.

Africans wore clothes crafted from animal skins/hides and traditional woven materials before the arrival of the European explorers and traders. In modern days, clothing plays an important role as a medium for negotiating visual differences across cultures (Rovine, 2009). These visual differences are crucial in the identification of traditions and cultures to facilitate cultural or social affiliations. Twigg (2009) observed that “clothes display, express and shape identity by infusing it with a direct material reality” (p.1).

According to Perani and Wayne (as cited in Akinbileje (2014)), clothes are mirrors of local cultures as they possess the potential to unpack various information embedded in print about self and personal worth, occupation, social status, and standard of economic value, as well as political power. In some societies, clothes are communicative tools used to display class distinction and strength through which elites establish, maintain, and reproduce positions of power and dominance over the weak and poor in a non-institutionalized form, which Assmann (2008) referred to as communicative memory.

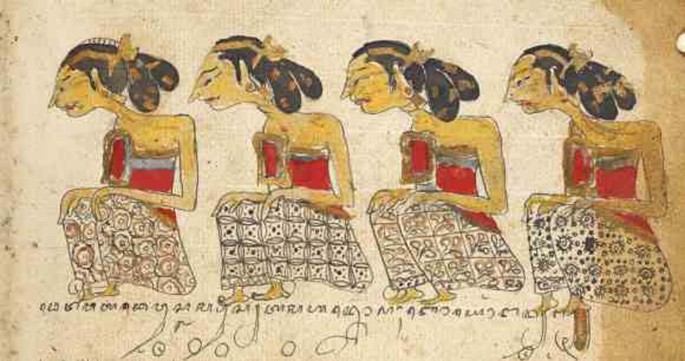

The ruling classes across societies have historically used clothing and symbolic artifacts to demonstrate their power and wealth using some form of sumptuary laws based on their social ranks including wealth and political power to reinforce social stratification and class boundaries (Wilson, 2016; DuPlessis, 2019). In Ghana for example, Akinbileje (2014) observed that kings and chiefs often wore clothes decorated with gold string patterns and coral beads to communicate their financial strength to the rest of the public including their rivals. This is evident with the colorful Kente cloth shown in Fig. 5, which was worn exclusively by the royals of the Ashanti Kingdom since the sixteenth century as a form of cultural representation of the Ashanti people.

King of Ashanti Kingdom wearing rich Kente cloth during festival in Ghana. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ashanti_chief_in_Ghana.jpg.

Each color or pattern weaved into the Kente textile carries strong information ranging from wealth, spiritual purity, and peace to healing and cleansing rituals, which demonstrates the cultural identity, values, and power of the Asante royals. Adom (2024) observed that Asante Kente captures the historical, political, and religious worldviews, values, and norms of the Ashantes linked to historical identity, culture, and philosophy.

In most African countries, the type and quality of clothes people wear are the immediate indicators of cultural diversity, socioeconomic status, and political power. The Kalabari people in Nigeria for example, are identified using the modified version of the Indian Madras cotton cloth; on the other hand, the use of Adire fabrics abroad directly signifies a Nigerian notion (Rice, 2015, p. 178). According to Honeycutt (2021) and McCracken and Roth, (1989), clothes contain linguistic codes embedded in their colors, designs, or composition as a means of communication where a certain class of society conveys both the official and cultural memory about themselves, cultural norms, social or political standing to the public to influences certain societal opinions.

Source link