Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia

Respondents characteristics

From a total of 384 disseminated questionnaires, 198 valid observations (52% response rate) were useful for analysis, and the majority of the respondents were males that account for 143 (72. 2%) whereas 55 (27.8%) were female respondents (see Table 2). And, the majority of them were youngsters under 18–35 years of age that accounting for 175 (79.3%). The survey indicates the youngsters are the majority of employees working and residing around cultural heritage which can be basic to apply cultural heritage conservation practices for better off.

Regarding place of residence and livelihood strategy of the respondents, 68 (34.3%), 52 (26.3%) and 44 (22.2%) reside in and around heritage sites namely, Ankober Medahnealem, Koremash and Goze whereas few respondents accounted for 34 (17.2%) lived in Angolela Kidanemihret area. Regarding the livelihood strategy people employed, the majority of the respondent led their household through employment in government offices followed by engaging in agriculture and working as a private employee accounts for 61.6%, 12.1% and 9.6% respectively (see Table 3).

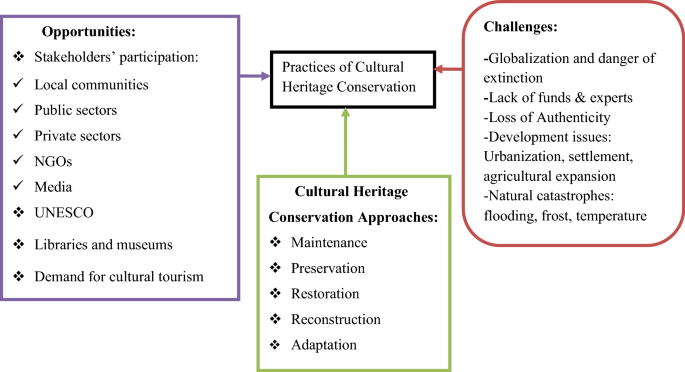

Practices of cultural heritage conservation

The research finding indicates that 12.1% and 30.8% of respondents strongly disagreed, and disagreed respectively whereas 33.8% and 7.6% of respondents agreed and strongly agreed regarding an attempt of cultural heritage conservation in the study areas. The result revealed that there is insufficient attempt to conserve the heritage. Similar to this study, in Africa and many developing countries, cultural heritage have been facing hindrances of multiple platforms in unplanned manner that didn’t account for heritages sustainable use [72]. Unlike the finding of the present study, Ekwelem, Okafor and Ukwoma [72] pointed that the preservation of cultural heritage properties enhances historical and cultural continuity, fosters social cohesion, enables to visualization of the past and envisioning the future, and hence it is indispensable for sustainable development. Another study that supports this argument revealed that a need for conservation of heritage is subjected to a desire to transfer away from object oriented conservation and preservation practices, and the theoretical commitment to social constructivism that consider heritage a socio-cultural process [73]. The aforementioned two findings assured that heritage conservation practices should not only prepare for their objective value like source of economy but also as a social and cultural process that could maintain history which in turn escalate social cohesion, promote identity and proud. The finding revealed that the local community has a sense of belongingness and identity to the cultural heritage as it is portrayed by the respondents’ response shown by 34.3% and 7.1% of agreement and strong agreement. This significant level of community belongingness and awareness about the cultural heritage will overpoweringly support the conservation efforts at heritage sites [74].

The practice of cultural heritage conservation in the study area is not based on research as 16.2% & 38.4% of the respondents strongly disagreed and disagreed in this regard. The present finding suggests that in-depth and strong research to develop conservation guidelines and undertake conservation activities in heritage sites. According to Garrod and Fyall [75], conservation management should consider timeliness and managerial prudence. The timeliness concept stated that conservation funds should be allotted in a timely fashion to save high conservation costs in the future. From the managerial prudence angle, parallel measures or techniques should be designed to prevent further deterioration [75]. Moreover, the study of Oevermann [76] scrutinized the “Good Practice Wheel” that is composed of management, conservation, reuse, community engagement, sustainable development and climate change, education, urban development, and research that expresses each of the good practice criteria spinning wheels which also needs the consideration of those criteria while practising heritage conservation. In this regard, the conservationist expert from ARCCH (personal communication, 21 June 2021) also underlined that,

Though there are efforts by the conservationists to undertake in-depth research, there are initiations mainly from the political leaders showing a commitment to conserve the heritage without adequate research and analysis.

Another participant from the Authority for Conservation of Cultural Heritage (Head, Conservators, personal communication, June 17, 2021) portrayed;

The basis and detrimental problem in the practices of conservation especially in cultural heritage is either lack of original material to conserve perfectly as it was or unavailability of raw materials that resemble originality which makes the conservation practice less effective. He added that the problem exacerbated by the lack of conservationists in the field makes the Ethiopian Heritage in danger.

Besides, regular follow-up of existing status for conservation hasn’t been made with 20.7% and 37.9% of strong disagreements and disagreements that revealed poor status of conservation. Similarly, capacity building training on heritage conservation is not delivered at different times to the communities, conservationists and other key stakeholders that are exhibited by a total of 65.7% level of disagreement (where 26.3 replied with strong disagreement and 29.4% replied with a disagreement scale). Only 17.7% of respondents were found in the agreement response category whereas 16.7% were unable to fall in the two categories either (see Table 4). Hence, the finding of this study revealed that there is a low-level practice of cultural heritage which needs to be improved. Analogues to this, the conservation of heritage requires the three most important elements of heritage conservation underlined by professionals (curators, academics and consultants) are training and expertise of maintenance staff, budget and financial planning, and conservation plan [77]. Conservation efforts should be monitored that could follow up information for condition, risks and value assessment, strengths and support strategic heritage planning regularly which in turn should be developed based on an inventory system that requires continuous monitoring [78].

Challenges of cultural heritage conservation

This study was also concerned with the investigation of the various barriers that hinder cultural heritage conservation practices for better management and sustainability of cultural heritage. Thus, to identify these factors, factor analysis was employed to extract the list of factors and to group each of the linear components onto each factor if found significant. A total of 22 items or linear component factors (variables) were employed after checking the reliability of items in the pilot survey. Those variables were coded as: 01-The local community have no positive attitude towards cultural heritage; 02- The local community are not concerned to the cultural heritage; 03- Population growth and settlement programs have impacts on cultural heritage of the area; 04- Conflict of interest among stakeholders to safeguard the cultural heritage; 05- A practices of heritage conservation without the involvement of professional; 06- Practice of illicit trafficking of cultural objects; 07- The cultural heritage is not promoted for sustainable tourism development; 08- Practice of farming in and around the cultural heritage; 09- Adequate budget/ financial allocation for conservation of cultural heritage; 10- Little concern of government and local authorities about the heritage; 11- Professionals lack enough commitment to engage in conservation practices; 12- Media failed to expose the problems of heritage to the community in time; 13- Travel agents and tour operators are negligent to the sustainability of heritage; 14- Inappropriate conservation practices of cultural heritage; 15- Lack of buffer zone demarcations of the heritage sites; 16- Natural catastrophes and climate variations (flooding, frost, acidic rain, storm, heat from the sun) deteriorate cultural heritage; 17- Development projects such as buildings, roads affect the sustainability of heritage; 18- The heritage hosts more than its carrying capacity during different events; 19- Funding agencies lack willingness to provide aids and loans to cultural heritage; 20- There is no regular monitoring and evaluation of cultural heritage status by the concerned body; 21- The growth of vegetation over the heritage, and 22- The heritage are challenged by biological factor such as rat and other biological organisms.

The assumptions of relationship, randomness and sampling adequacy were checked in the analysis of exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

The descriptive statistics revealed that all the 22 linear component factors or variables have a mean value greater than 3 with a range varied from 3.41 to 3.95 for a total of 198 valid observations made for analysis. And, there was no missing data in the analysis.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (see Table 5) also indicated that the sample size employed was adequate and the assumption is met with the KMO and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity value of 0.768 and Sig. = 0.000. A value varies between 0 and 1 where the value close to 1 indicates that patterns of correlations are relatively compact and so factor analysis should yield distinct and reliable factors. Kaiser [79] recommends accepting values greater than 0.5 as acceptable. Hence, the current value of KMO Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity meets the assumption [79].

The communalities table also presented the relationship of one of the variables with the other variables before rotation with which a value greater or equal to 0.30 indicates the employed sample is acceptable and results will not be distorted. The current finding has confirmed this assumption of factor analysis with the value ranging from 0.315 to 0.784 which is significantly above 0.30.

Factor extraction and variance explained

The present finding indicated that 59.51% of the total variance is explained by the seven factors extracted out of 21 linear components variables included in the model with Eigenvalues greater than one. Hence, the Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings indicated that the first factor contributed about 14.726% and the 2nd contributes 9.412% whereas the 3rd and 4th factors accounted for 8.808% and 7.503% of the variance explained. The 5th, 6th, and 7th factors contributed to about 7.222%, 6.509% and 5.325% of variance explained in cultural heritage conservation (see Table 6).

Factor rotation

The rotated factor matrix indicates the rotated component matrix (also called the rotated factor matrix in factor analysis) which is a matrix of the factor loadings for each variable on to each factor. The component loadings for each factor are positive that shows the positive relationship between the variable and each principal component. The values below 0.45 were suppressed while extracting the factors, and are not displayed in the rotated component matrix and the factor loadings were sorted by size. The orthogonal rotation was used with the assumption that the variables are independent of each other [80]. Before rotation, most variables loaded highly onto the first factor (21.554% variance explained) and the remaining factors didn’t get a look in. However, the rotation of the factor structure has clarified things considerably with the equivalence of variance explained. As can be depicted in the rotated matrix table, there are seven components or factors that have been extracted as a factor hindering the management of cultural heritage conservation. Hence, Principal Component factor analysis with Varimax rotation was conducted to assess the underlying structure for the 22 items of the challenges of cultural heritage conservation practices. The assumption of independent sampling, normality, linear relationships between pairs of variables, and the variables being correlated at a moderate level were checked.

Seven factors were extracted after rotation, the first factor accounted for 14.726% of the variance and was composed of seven items related to lack of proper management, monitoring and evaluation, whereas the second factor accounted for 9.412% that consisted of a cluster of three variables that were related to lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement. The third factor accounted for 8.808% and it comprised of two items which are related to lack of government concern and professional commitment. The fourth factor consisted of three items and it is related to lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion for sustainable development and accounted for 7.503%. The group of two items related to poor destination management and conservation practice make the fifth factor that accounted for 7.222% whereas the sixth factor accounted for 6.509% and comprises two items that are related to natural catastrophes and agricultural practices (see Table 7). The 7th factor encompasses only a single variable that is related to the lack of communities’ positive attitudes towards cultural heritage.

Table 7 displays the items and factor loadings for the rotated factors, with factor loadings less than 0.40 omitted to improve clarity. Similar to the present study, heritage properties can be affected by the impacts of visitors such as overcrowding which may result in wear and tear including trampling, handling, humidity, temperature, pilfering and graffiti [75].

Mathematical representations of factor loadings

Like regression, a linear model of the mathematical equation can be applied to the scenario of describing a factor. The factor loadings are represented by b ‘s. According to Field [80], the equation can be written as.

Fi = b1X1i + b2X2i + … + bnXni.

Where Fi is the estimate of the ith Factor; b1 is the weight or factor loading of variable X1, b2 is the factor loading of variable X2, bn is the factor loading of variable Xn, and n is the number of variables.

Accordingly, it was stated that seven factors were found underlying the construct Factors affecting cultural heritage conservation. Consequently, an equation can be constructed for each factor in terms of the items that have been measured.

Factor 1 = 0.671(X1) + 0.668 (X2) + 0.664 (X3) + 0.626(X4) + 0.571 (X5) + 0.571 (X6) + 0.485(X7).

By substituting the mean value of each item (question), the approximate percentage variance that factor 1 can explain can be calculated.

Factor1 = 0.671(3.58) + 0.668 (3.36) + 0.664 (4.33) + 0.626(3.60) + 0.571 (3.60) + 0.571 (2.88) + 0.485(2.86) = 14.2

Factor 2 = 0.742(X8) + 0.710(X9) + 0.576(X10) = 0.742 (4.53) + 0.710(4.42) + 0.576(4.72) = 9.23.

Applying similar formula for the remaining factors, and adding the calculated values together, or the summation of all factors will be a total of 58.51 which means using the mathematical equations, the seven factors together can explain 58.51% of the variance. As explained before in the total variance explained in Table 7, in the rotated sums of squared loadings column, it has been said that the seven components explained 59.51% of the variance. Hence with a minor difference, values calculated from the equation and summations of a percentage of variance in the total variance explained Table 7 provide an approximately similar result. The difference may be resulted either from using the approximate values after the decimal point or the factor loadings less than 0.4 that were suppressed.

After conducting the exploratory factor analysis and extracting the seven factors, the multiple linear regressions was applied to confirm which factors affect the practice of cultural heritage conservation.

Assumptions of multiple linear regression

- 1.

The relationship between the independent variable and dependent variables is linear. This assumption was confirmed as it is reflected by the scatter plot that showed the relationship is linear for all independent variables: lack of proper management, monitoring and evaluation, lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement, lack of government concern and professional commitment, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion towards sustainable development, poor destination management and conservation practice, natural catastrophes and agricultural practices, and the local community have no positive attitude towards cultural heritage conservation.

- 2.

There is no multicollinearity in the data set. Multicollinearity exists when the correlation coefficient r between independent variables is above 0.80. Hence, no independent variable was found to have multicollinearity problems with each other with all below 0.80 where the highest Pearson correlation value of 0.688. Besides, the multicollinearity issue can be checked by VIF and tolerance level where VIF is below 10 and tolerance level > 0.20 [81]. Hence, VIF and Tolerance are found within the acceptable region.

- 3.

The values of the residual are independent. The residuals of the data set in the sample stratum were found independent or uncorrelated which can also be tested based on Durbin-Watson statistics (above one and below 3). The Durbin Watson statistics is 1.821.

- 4.

The assumption of homoscedasticity: the assumption that shows the variation in the residual is a similar constant at each point of the model. As it can be shown, the closer the data points to a straight line when plotted, the points are about the same distance from the line meaning the data points have the same scatter. This can be shown by the normality probability curve of the scatter plot (see Fig. 3).

- 5.

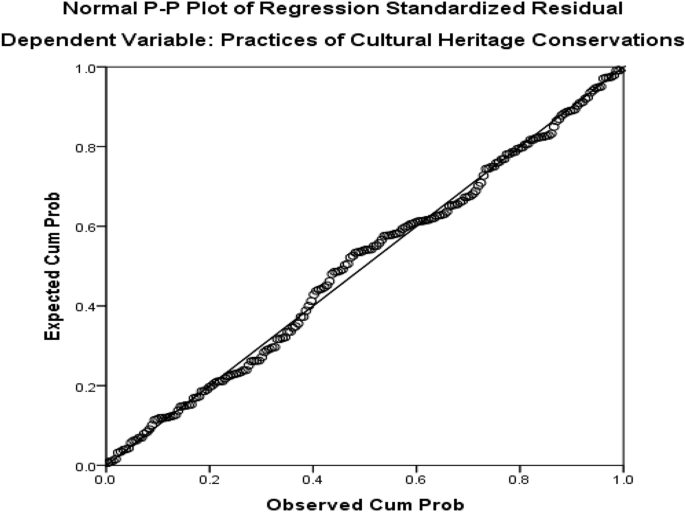

The values of the residual are normally distributed. This assumption can be tested by looking at the p-p plot for the model. The closer the dote lies to the diagonal line; the closer to normal the residuals are distributed. The normal p-p plot dotes (see Fig. 4) line indicates that the assumption of normality has not to be violated.

Regression results

The Pearson`s correlation table indicates (see Table 8) that there was a significant relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable i.e. cultural heritage conservation at a p value of 0.05 level of significance. However, lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement, poor destination management and conservation practice and lack of the local community positive attitude towards cultural heritage were not significantly correlated with the cultural heritage conservation practice (r = 0.057, sig = 0.212; r = − 0.008, sig. = 0.458 and r = 0.016, Sig = 0.410). Thus, the indicators were removed from the regression model.

The Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) table (see Table 9) exhibits the goodness of fit of the model and revealed the model is appropriate and the introduction of the independent variables has improved by at least one predictor (P = 0.001) significant at 1% level of significance. Thus, the model is the best-fitted model presenting the regression that presents the significant independent variables that significantly explain the dependent variable.

The model summary shows the predicted variable i.e. practices of cultural heritage conservation is explained by the introduced independent variables viz., natural catastrophes and agricultural practices, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking, promotion towards sustainable development, lack of government concern and professional commitment, and lack proper management, monitoring and evaluation accounted for 7.9% with an adjusted R square value of 0.079 (see Table 10). The variance explained in the model summary table is also supported by the coefficients table that exhibited some of the extracted factors that were significant.

The coefficient result shows that the largest β value is the greatest predictor of heritage conservation. Among the independent variables, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion towards sustainable development was found the most significant factor affecting practices of cultural heritage conservation (β = − 0.213, p < 0.05) followed by natural catastrophes and agricultural practices (β = − 0.132, p < 0.05). Besides, lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement was the factor found to be significant β-value (β = 0.179 & Sig. = 0.007). Furthermore, there was a negative relationship between lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and promotion towards sustainable development, and natural catastrophes and agricultural practices with the predicted variable.

As far as this study was concerned, lack of community concern, illicit trafficking and lack of promotion towards sustainable tourism development with β = − 213; p. = 0.002 and natural catastrophes and agricultural practices in and around the cultural heritage with β = − 0.132; p = 0.026 were found to be significant challenges hindering the heritage conservation practices (see Table 11). This finding was confirmed by the previous studies that revealed air pollution; biological causes like invasive intervention, humidity and vandalism have negative consequences on the survival of heritage tourism. The present finding was also in line with the findings of Irandu and Shah [82] that portrayed the cultural heritage conservation of Kenya faced challenges such as funding, poor enactment of policies, land grabbing and lack of adequate trained personnel. Besides, another finding revealed that tackling the calamities of climate change mainly global warming and extreme weather events combined with the implementation of varied strategies to moderate the impact of a growing tourist demand towards heritage sites become the growing problem in the conservation efforts of cultural heritage conservation which supports the present finding [83]. This finding also revealed the land use issue is an emerging problem for conservation. Therefore, the present study underlines that effective planning, proper land use strategy and environmental conservation policies shall be enhanced by the local and national governments.

Unlike the present study, as noted in the work of Eken, Taşcı, and Gustafsson [16] public participation along with governmental strategies is vital to deciding preventive conservation. Their finding indicated that local communities have an awareness regarding the significance and preservation of the World Heritage Site of Visibility, but they were not adequately cognizant of the practical aspect of preservation. The other issues raised by the authors are difficulties concerning guidance and promotion of regular maintenance which is also similar to the present study. Besides, restoration works have been carried out without a detailed report of the current condition of the cultural heritage [16]. On the opposite, the interview was found in line with the aforementioned previous study revealing the disintegration of the heritage concerned authorities, the poor intervention of the government and inadequate collaboration of the local and regional governments with the local communities. Besides, the political implication of understanding the heritage also nailed our challenge in the conservation of cultural heritage. Similar to the present finding, the study scrutinized owing to conflicting claims, representations and discourse of urban heritages become contested [84]. Unlike the present finding, the study of Tweed and Sutherland [85] indicates that conserving heritage properties contributes to the sustainability of the built environment, and it is a crucial element of the cultural identity of the community which describes the character of a place.

Moreover, lack of stakeholder involvement and population settlement was identified as a significant challenge with β = 0.179; p = 0.007 in the present study. The previous findings revealed that the lack of collaborations to date in terms of managing the assets between the local authority and other stakeholders was found a significant challenge in cultural heritage conservation [86]. The findings of this study were supported by the findings of the previous study on the adaptation of land use for new purposes and functions, especially for the heritage buildings which demand new strategies for the indoor quality and efficiency of heritage for the new functional use was found the challenge that affects heritage conservation and management of heritage sites [83]. To overcome this problem, stakeholder collaboration and involvement, community empowerment and the adaptive reuse approach should be adopted that in turn increases the tourism demand and receipts which again escalate the multiplier effects within the industry combined with the job creation [87] and livelihood diversification through the enhancement of conservation enterprises around protected areas [88]. It is argued that cultural heritage sustainability relies on training and education that can produce competent human capital who are in charge of heritage protection and promotion [89]. The cultural heritage understudy is facing various natural and manmade problems which were verified by the interview made with officials of ARCCH who are working at the department of Heritage Restoration and Conservation (Personal communication, 21 June 2021) that revealed structural problems of the heritage authority from federal to the local level, lack of skilled manpower, and lack of clear proclamations and guidelines regarding private heritage conservation. This finding was supported by the technical aspects such as limited availability of experts (lack of skilled forces, absence of educational training for new skills, and lack of technical staff in the heritage maintenance team) and availability of original or authentic materials were the major constraints in conservation projects [90]. Besides, the interviewees added lack of sufficient funds for restoration and conservation and the difficulty of conservation of heritage in and nearby urban areas due to urbanization and urban renovation were significant challenges for conservation. In line with the interview, the findings of Dias Pereira et al. [83] pinpointed the conservation of cultural heritage and the maintenance of its original characteristics and identity which could have been exacerbated by the unavailability of raw materials for conservation. Moreover, the unavailability of raw materials for restoration and maintenance of heritage, and keeping authenticity was found a very serious problem in the applicability of cultural heritage conservation practices [91]. Besides, there is an increasing interest to replace old cultural heritage with modern buildings, and hiding movable heritage are problems in escalating conservation efforts. An ideal example is the church of Ankober Medahnealem Church where only remnants or ruins of buildings are visible and the historical ruins of old church was replaced with the new modern buildings. Generally, the finding of the present study indicates the various challenges that should be overcome to assure the sustainability of cultural heritage. This was also supported by the study of [85], whose heritage conservation theme encompasses technical, environmental, organizational, financial and human issues.

Source link